Unpacking the “Trailer”: The People and Purpose of Colossians 4

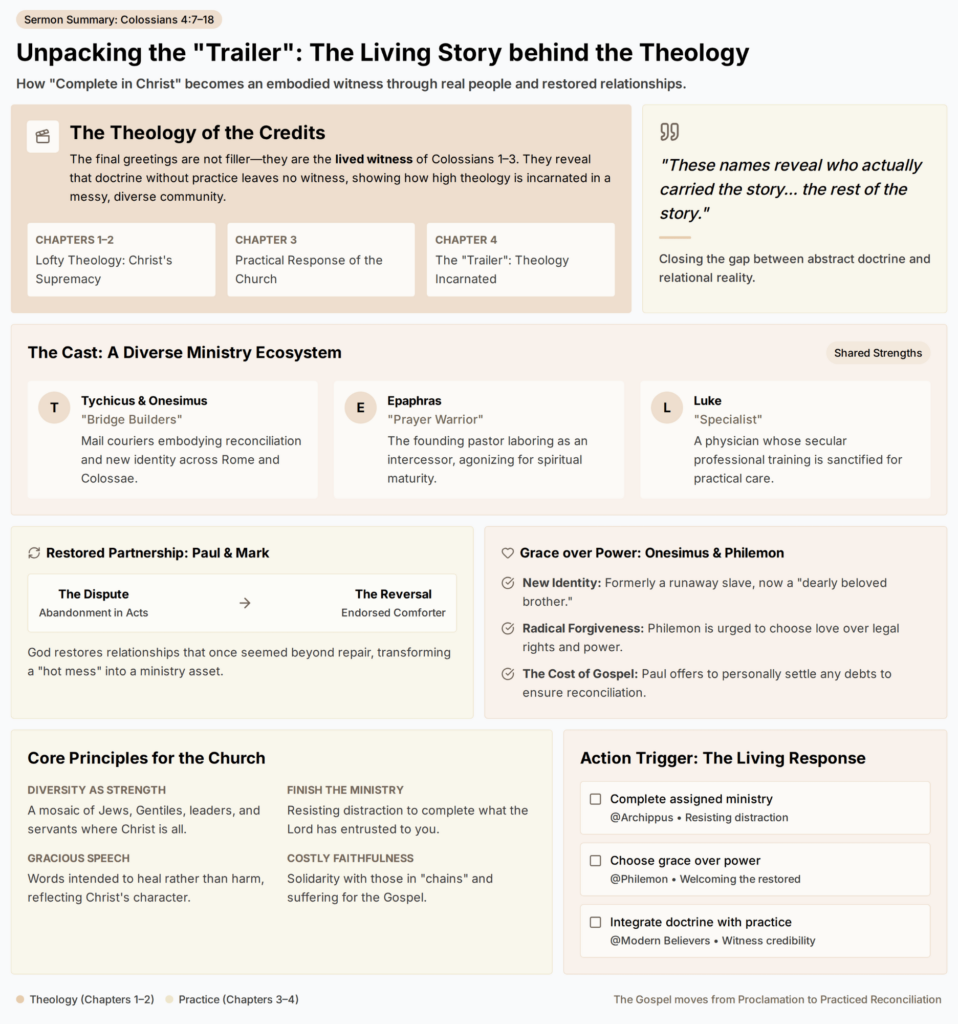

This sermon closes an expository journey through Colossians by focusing on 4:7–18, the “credits” of the letter that are often skimmed or skipped. The pastor frames the passage as the “trailer” that reveals the living story behind the theology and practices already covered.

He contrasts Colossians 1–2 (the “lofty” theology: Jesus is fully God; reconciliation through Christ’s blood; believers are complete in Christ; Christ disarmed spiritual powers) with Colossians 3 (the practical response of the church to its position in Christ) and Chapter 4 (recently emphasizing gracious speech whose aim is to heal, not hurt).

He notes that many readers treat the closing list of names as incidental, but insists it is the message itself: a window into the people, conflicts, reconciliations, and redemptions through which the gospel becomes visible and embodied.

The Overlooked Significance of the Final Greetings

The pastor argues that the names and greetings in Colossians 4:7–18 function like the end credits of a film: most stand up and leave, yet those credits reveal who actually carried the story. He admits he has often overlooked these names and thereby missed “the rest of the story,” invoking Paul Harvey’s phrase to underscore the point.

The sermon’s thesis: the final greetings are not filler. They complete the letter’s arc by displaying how “complete in Christ” (Chapters 1–2) becomes lived witness (Chapters 3–4) among real people—people marked by past failures, present faithfulness, and ongoing restoration.

In this section, the pastor situates the close-reading of names within the broader structure of Colossians, showing how doctrine without practice leaves no witness, and how this concluding “trailer” invites the church to see theology incarnated in community.

The Cast of Characters: A Diverse Ministry Team

The greetings introduce a diverse, multi-role ministry team surrounding Paul while he is in prison:

- Tychicus and Onesimus (“bridge builders”): They serve as trusted mail couriers, traveling from Rome to Colossae with two letters—the communal letter to the Colossians and the personal letter to Philemon. Their role is not merely logistical; they embody reconciliation and new identity as they deliver the message.

- Epaphras (“prayer warrior”): The pastor of Colossae who originally sought Paul’s help when false teachings threatened the church. He is depicted as agonizing in prayer, laboring as an intercessor—empathetic, persistent, and deeply invested in the spiritual maturity of the believers.

- Luke (“specialist”): A physician who employs his professional training to care for the body of Christ in tangible ways. His secular skills are sanctified for ministry, highlighting that the team’s strengths span spiritual intercession and practical healing.

This cast exemplifies a ministry ecosystem where varied gifts—administrative reliability, intercessory depth, professional competence—converge to sustain the church.

Reconciliation and Redemption in the Early Church

The pastor spotlights two relationship arcs that reveal the gospel’s reconciling power in messy realities:

- Paul and Mark: Acts 15:37–38 recounts a sharp dispute—Mark abandoned a mission, Paul refused further partnership, and Barnabas (Mark’s relative) chose to continue with Mark, resulting in a ministry split.

- The Colossians 4 greetings reveal a reversal: Mark reappears during Paul’s imprisonment as a comforter, and Paul now endorses him. The text itself doesn’t narrate the process, but the outcome signals real reconciliation.

- The pastoral takeaway: the early church experienced discord; it was a “hot mess.” Yet God restores relationships that once seemed beyond repair.

- Onesimus and Philemon: Onesimus had run from Philemon’s household; under Roman norms, his life could be endangered. At the public reading, he stands beside Tychicus as a “dearly beloved brother,” while Philemon—an influential leader in that same church—holds Paul’s personal appeal urging him to receive Onesimus not as a slave but as a brother in Christ.

- Paul acknowledges the offense and even offers to repay any debt, pressing Philemon toward love, forgiveness, and new dignity grounded in Christ’s lordship.

- The pastor clarifies the historical nuances of servitude in the Roman world (often debt-based, with eventual paths to freedom) without endorsing later chattel slavery.

- He notes that Philemon apparently accepted the appeal, allowing the letter to be circulated—hence its presence in the New Testament—demonstrating grace over rights and power.

Additional threads include Nympha’s hospitality—opening her house for the church—and Archippus’s exhortation: “See to it that you complete the ministry you have received in the Lord.” Paul’s closing, “I, Paul, write this greeting in my own hand. Remember my chains,” anchors these appeals in his own costly faithfulness.

His example shows he did not ask for the chains to be removed, but for an open door where he was, challenging believers who start but struggle to finish amid limitations, sufferings, and distractions.

The Living Story: Theology in Action

When the Colossian letter is read aloud, the room is filled not only with doctrine but with living testimonies embodied by the very messengers present. Onesimus, formerly a runaway, is publicly named as a brother; Philemon, seated among the congregation, holds Paul’s separate letter that calls for a response consistent with Christ’s supremacy.

In that moment, theology confronts real wounds and concrete decisions. The supremacy of Christ is no longer abstract—it reshapes relationships and challenges power dynamics. Paul refuses to command compliance; instead, he appeals to Philemon’s conscience in Christ, offering to settle debts and directing him toward grace, forgiveness, and a recognition of Onesimus’s new identity.

The gospel thus moves from proclamation to practiced reconciliation, revealing its cost and its transformative power within the gathered church.

Key Takeaways for the Modern Believer

The sermon crystallizes several applications:

- Diversity as strength: The ministry team includes Jews and Gentiles (e.g., Luke), leaders and servants (e.g., Nympha, Onesimus), specialists and intercessors. Their differences form a mosaic in which “Christ is all and is in all” (Colossians 3:11).

- Doctrine fuels practice: Without the theology of Chapters 1–2—Christ’s supremacy, the believer’s completeness—the practices of Chapters 3–4 lack power. With theology but without practice, witness is compromised.

- Gracious speech as healing: Chapter 4’s call to grace in words is restorative, aiming to heal rather than harm.

- Finish the ministry given: Archippus’s charge applies broadly—complete what the Lord has entrusted. The book leaves believers both secure (“our life is hidden in him”) and sent to live out their faith in tangible, relational ways.

- Grace over power: The Philemon episode models aligning authority and rights under Jesus’s lordship, choosing reconciliation, forgiveness, and dignifying others in Christ.